Author: Lindsay Sheronick Yearta (Winthrop University)

The winter break over, students and teachers are gearing up for the second semester of the year. As students stream into the hallways and clamor into their classrooms, the excitement is contagious. How do we keep our students excited about learning long after the first bell has rung? One way to increase engagement in learning is to integrate technology into the curriculum (Mills & Levido, 2011) to provide students with increased opportunities to collaborate and learn in authentic ways. Provided that students have access to a device and the Internet, thinking and learning can be transformed into a more collaborative, connected, and engaging endeavor.

Using digital flyers in the classroom is one way in which students can use technology to increase engagement and deepen their learning. Take for example, the students in Mr. John-Joseph’s seventh grade social studies class. At the beginning of the Cold War unit, Mr. John-Joseph realized that some of his students were struggling with the more difficult concepts. After talking to one of his colleagues who used Smore as a presentation tool with his students, Mr. John-Joseph thought about how he could have his students use the features of this tool to increase thinking and learning in a digital space.

Using Smore as a tool for thinking and learning

Smore is an easy to use website that allows users to create digital flyers. In addition to creating digital flyers or posters, this site can also be used as a digital note-taking pad of sorts. Students can use this site to collect and reflect upon meaningful information. Instead of one-dimensional, traditional note taking, students can insert videos, links to other sites, images, and can share their thinking and learning with peers.

In other words, Smore can be used as a tool to help students create digital concept maps in the classroom. Concept maps have many synonymous names such as mind maps, semantic maps, and learning logs. These graphic organizers allow students to use the space to record what they already know about a topic, activating schema (McLaughlin, 2010). Students are also able to take notes as they progress through the unit, and reflect on their learning upon completion of the unit. In this way, the mind map can grow with the student. A problem arises, however, when students are unable to fit the entirety of their thoughts on a traditional paper mind map.

Creating and maintaining the mind map in a digital space allows students to document their learning, reflect upon and question their newfound knowledge, and collect links to supplemental materials all in one place. Embodying the principles of Universal Design for Learning, the teacher can help to build or activate schema for all students using this digital tool (Lapinski, Gravel, & Rose, 2012). Specifically, if students are lacking in background knowledge of a specific topic, they can easily find videos and websites to help build that schema.

With Smore, after users create an account and log in with an email and a password, they can create up to five free flyers. Students can sign up for individual Smore accounts or can create flyers through the teacher-created educator plan. The educator plan is $39 a year and allows for unlimited flyer creation for educational purposes. In this way, students and the teacher alike could use one login name and password to create unlimited flyers.

Once a template is selected, the user can add a variety of components such as audio, text, picture, form, and gallery onto the flyer by clicking on the appropriate buttons at the bottom of the flyer. Students can then immediately begin inserting information. Clicking the text button offers students a chance to take notes or reflect on a particular concept. There are several word processing features that students can use such as making the font bold or in italics. Students can insert text in a bulleted or numbered list format and can also hyperlink text.

A benefit of Smore is the ability for the creator to access analytics. Analytics provide information such as the geographic location of the viewer, the number of times users have clicked on links, and the frequency of users reaching the end of the infographic. Through the examination of this information, users have a visual understanding of the scope of their words as they gain access to information such as frequency and an awareness of a wide audience.

Smore Learning in the Classroom

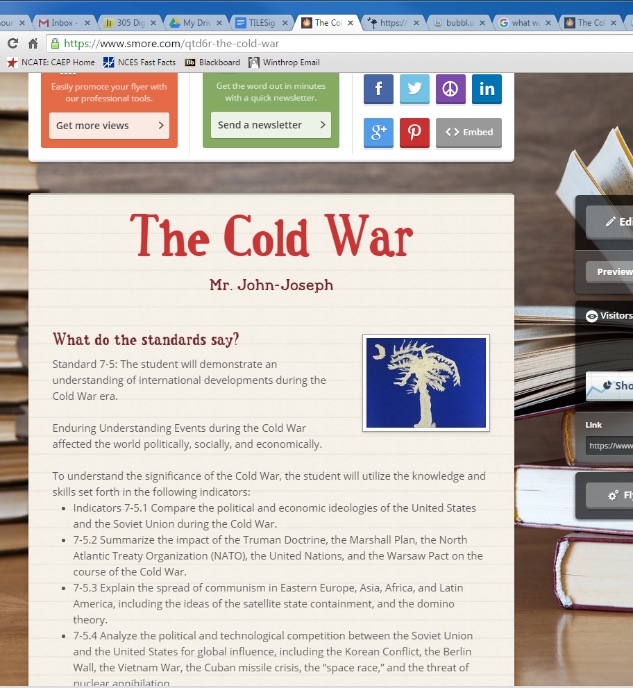

After he decided to use Smore in the classroom, Mr. John-Joseph began by creating a sample infographic using Smore to show his students (see figures 1 and 2).

He told his students that this was not a presentation, or even a finished product. Rather, this was a repository of his learning. Mr. John-Joseph pointed out that he included the state standards as his first text box so that he could continuously check and see what his teaching goals were. He used it as a roadmap to guide instructional planning and delivery. He told students that when they created their own Infographic, they could also include the state standards or unit objectives to help them gauge their own progress in learning.

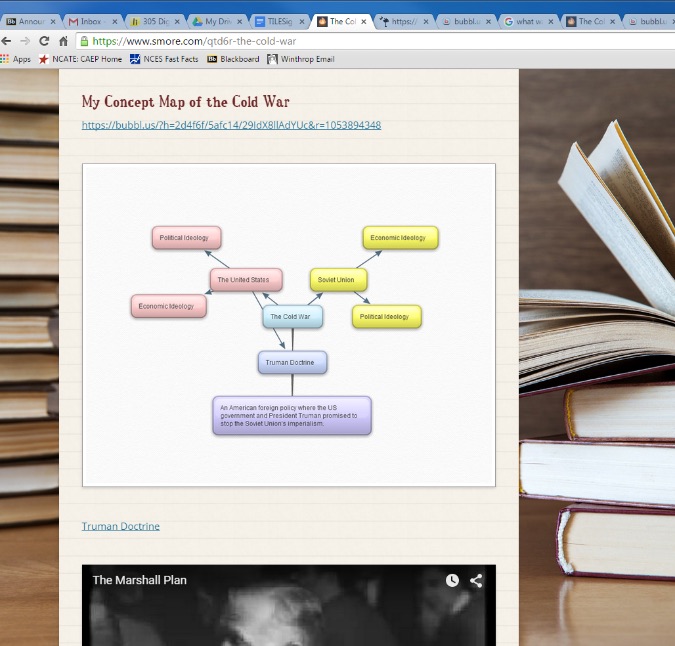

Mr. John-Joseph also started a concept map, using the site Bubbl.us. He linked his in-progress concept map of the Cold War in his Smore and also inserted a screenshot to show students what it looked like (see figure 2). He thought it was important to show students his work in an in-progress state. He wanted to demonstrate to students that his knowledge would grow as he investigated topical concepts. Additionally, Mr. John-Joseph shared how he needed to research information on the Truman Doctrine, because he was not certain of the details. After finding a quality website, he linked the site to his page. He could then review the notes, from his smartphone, anytime he needed to, including while he was waiting in line in the cafeteria. Mr. John-Joseph also found a short video clip on the Marshall Plan and linked it in his Smore.

After reviewing the components of his own flyer, Mr. John-Joseph asked his students to take our their devices and go to the Smore website. He explained that students would take notes using the online format in a way that was personally relevant. He reiterated that these flyers were not finished products. In fact, they were to serve as works in progress. They would be repositories of student thinking. These flyers were going to grow in breadth as the unit progressed. Mr. John-Joseph created a Google Doc so that each student could provide a link to his/her personal digital flyer in one, communal place. This would enable Mr. John-Joseph to monitor students’ progress throughout the unit. Additionally, students would had access to one another’s thinking and could link personal flyers to peers’ flyers.

Marquis, one of the students in Mr. John-Joseph’s class, was struggling with the concept of the Truman Doctrine. So, he searched for additional information and found a website with valid information. He decided to hyperlink the site on his digital flyer. He typed Truman Doctrine, used his mouse to highlight the phrase, and clicked on the hyperlink button. He then put the website link in the box and clicked link. The website, with background information, was then hyperlinked to the phrase Truman Doctrine, just as it is here.

Some students prefer to listen to and view information instead of reading. To add a video, students click on the video button and are then prompted to add the link. After inserting the link, students click embed. The video is then placed in the digital flyer. Carolyn found this hyperlinked video on the Marshall Plan and placed it in her flyer. One of her classmates liked the video so much that he used the share button on Carolyn’s flyer placed it in his flyer as well.

As students progressed through the Cold War unit, using the digital flyer, Mr. John-Joseph noticed that students appeared to be more engaged. Students were able to locate materials on individual reading levels and utilize supplemental materials as well. Many students were curious about classmates’ digital flyers and while exploring, had access to increased materials. While Mr. John-Joseph still required his students to read portions of text from the class textbook, he noticed that students seemed better able to grasp the information. He attributed this increased success to students’ augmented background knowledge.

Final thoughts

While Smore can be used for a myriad of purposes such as presentation tools, expert projects, digital mind maps, and for ongoing assessment (Yearta & Mitchell, 2016), in this article, we focused on using the digital flyer for the purpose of creating and maintaining digital mind maps.

An additional feature of the digital learning is that students can share their learning with family, friends, and people from their community with the touch of a button. Students can receive nearly instantaneous feedback and sharing their knowledge with others makes the learning that much more authentic.

References

Lapinski, S., Gravel, J., & Rose, D.H. (2012). Tools for practice: The Universal Design for Learning guidelines. In T.E. Hall, A. Meyer, & D.H. Rose (Eds.), Universal Design for Learning in the classroom: Practical Applications (pp. 9-24). New York: The Guilford Press.

McLaughlin, M. (2010). Content area reading: Teaching and learning in an age of multiple literacies. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Mills, K.A., & Levido, A. (2011). iPed: Pedagogy for digital text production. The Reading Teacher, 65, 80-91. doi: 10.1598/RT.65.1.11

Yearta, L. & Mitchell, D. (2016). Infographics: More than just digitized posters. Reading Matters, 16, 66-69.