Author: Lindsay Sheronick Yearta, University of South Carolina Upstate

As one of the National Reading Panel’s five components of literacy (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [NICHD], 2000) and as a component that shares a strong link with students’ reading comprehension (Graves, 2004; NICHD, 2000), vocabulary instruction has always been an essential part of the school day. Furthermore, vocabulary acquisition and retention has been receiving increased attention recently (Manyak, Von Gunten, Autenrieth, Gillis, Mastre-O’Farrel, Irvine-McDermott, Baumann, & Blachowicz, 2014). While the literacy community is witnessing a renewed interest in vocabulary instruction, my interest in digital vocabulary study began a few years ago in a graduate course at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. I was learning about an interactive word wall (Harmon, Hendrick, Wood, Vintinner, & Willeford, 2009) and, as a fifth grade teacher with a multitude of standards to teach, I thought about how I had allowed vocabulary instruction to take a backseat in my classroom. I was interested in the interactive word wall and wanted to integrate my love of technology. I knew how much my students enjoyed using digital tools and I wondered if an interactive word wall was beneficial for student learning, what might adding digital tools do to the process?

Research Questions

The aim of the study was to determine what effect, if any, digitizing the word wall had on students’ vocabulary acquisition, retention, and/or motivation. Specifically, the research questions were:

- What effect does the use of a digital word wall have on students’ vocabulary acquisition when compared to the use of a non-digital word wall?

- To what extent do students retain knowledge of the vocabulary words when using the digital word wall when compared to the non-digital word wall?

- What are teachers’ and students’ perceptions of the digital word wall?

Methods

The study was conducted in two fifth grade classrooms using an explanatory mixed-methods approach (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). Quantitative data were collected in the form of pretests and posttests administered at the three week, six week, and eight week marks. These tests were comprised of multiple-choice tests (Graves, 2009) and a vocabulary knowledge scale test, validated by Wesche and Paribakht (1996) and found to be an accurate measure of student vocabulary knowledge. The quantitative data helped to answer research questions one and two. Qualitative data were used to answer research question three as well as to help explain the quantitative data. The qualitative data were collected in the form of interviews with participating teachers and several of the participating students.

The fifth grade students engaged in six weeks of vocabulary instruction on Greek and Latin roots. Each student was able to experience three weeks of instruction with a non-digital word wall and three weeks of instruction with a digital word wall. As aforementioned, students were given a pretest, an assessment at the three-week mark, the six-week mark, and the eight-week mark (to test for retention).

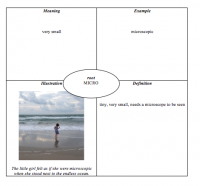

To maintain consistency, students worked on modified Frayer models (Yearta, 2012) with both the non-digital and digital word walls for 20 minutes a day (see Figure 1 for an example of a modified Frayer model and an explanation of the components).

Figure 1.

In regards to the digital word wall, students also had access to digital tools and used PBWorks as a forum to post and discuss their models. PBWorks is a wiki and is free for classroom teachers with up to 100 users. Additionally, students had access to digital tools such as Greek and Latin root websites, digital dictionaries, and countless photographs and images (see Figure 2 for links).

| Digital Tools | Links |

| PBWorks | https://plans.pbworks.com/academic |

| Greek and Latin root websites | https://www.learnthat.org/pages/view/roots.htmlhttps://www.msu.edu/~defores1/gre/roots/gre_rts_afx2.htm |

| Digital Dictionaries | http://www.merriam-webster.com/http://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/ |

| Photographs & Images | http://search.creativecommons.org/ |

Figure 2.

Findings

Findings from the study indicate that the word wall is a thorough method to instruct students on Greek and Latin roots. Posttest scores were significantly higher than pretest scores in the multiple-choice assessment and the vocabulary knowledge scale assessment. In regards to the digital versus non-digital methods of instruction, there were several interesting findings. First, this study did not prove a significant difference in students’ simple recall of Greek and Latin root meanings. However, when considering deeper levels of word meaning, as indicated by the vocabulary knowledge scale, the digital word wall was a more successful method of vocabulary instruction. In regards to retention, the only significant gains were from pretest to eight-week posttest gains.

Both participating teachers, regardless of personal comfort with technology, were motivated to use technology in their classrooms for the sake of their students. They also felt that students were more engaged when they were working on the digital word wall, one student mentioned that she was better able to remain focused on the computer, “I can stay focused on the reading.” A student from the other participating class mentioned how she would lose focus when dealing with the hard copies, “You get tuned out after a book. Like, after so many pages, you get tuned out.” However, she enjoyed that with a computer she could go through, “different pages” and “different sites” while she was constantly “learning something new.” Additionally the teachers felt that the students enjoyed the digital word wall more. One of the participating teachers noted, “When the computers cooperated, they enjoyed the digital way more.”

Data from student interviews indicated that students felt the digital word wall was faster, easier, and more motivating than the non-digital word wall. While faster certainly does not mean better, the interviewed students seemed to enjoy this perceived benefit. A student specifically stated, “you just click on a button, you can just start typing, and it’s up. Then you gotta get your root and go!” Several of the students mentioned the ease of locating information with the digital word wall and one of the students mentioned how he enjoyed being able to “open new tabs to do more than one at a time.” The data also seemed to suggest that students found the computer to be more motivating. Students felt like they could make a mistake on the computer, as they felt they had the option to retry until it was correct.

Successes

This project had several outcomes that could be viewed as “successes.” Both the digital and non-digital word walls were much more effective than the previous method of vocabulary instruction at the elementary school in which the study was conducted. Furthermore, both the students and the teachers discussed how the digital tools that students used for the digital word wall were helpful. Students could use the online dictionaries to look up the meanings of words without having to possess a strong grasp of sound-symbol relationships. Students could find appropriate photographs or clipart to serve as visual representations of their root words. Additionally, students had greater access to their digital word walls than the non-digital word walls. This would be especially helpful for students with iPads or laptops. The students could access their digital word walls from anywhere as long as they had Internet access.

Vocabulary instruction should be engaging and active (Manyak, et al., 2014; Taylor, Mraz, Nichols, Rickelman, & Wood, 2009) and the participating students and teachers felt that the digital word wall was. One of the teachers mentioned how, while she didn’t know if she’d use the non-digital or digital word wall the following year, she would “definitely do one of those over what we used to do.” She believed that having students engaged in the word wall was beneficial, “I think they learned more from both of them, more than anything we’ve ever done before.” A student, in a separate interview, stated how he enjoyed working on each of the word walls. He even mentioned how the word walls were better than the method his class had been using to study vocabulary.

Challenges

This study was conducted on a small scale. There were two participating fifth grade classes, situated in a suburban area in the southeast. The time span of the study was only 8 weeks. It would be interesting to see this study replicated with a larger, multi-grade group over a longer period of time. An additional consideration would be conducting the study in a 1:1 school.

Final Thoughts

Of course, some students and teachers are going to prefer the more traditional, non-digital word wall. The digital word wall is not being presented as the only method of vocabulary instruction; it is simply one more tool that teachers can add to their repertoire. Furthermore, the access to and experience with the digital tools that accompanied the digital word wall may transfer into other academic areas.

We know that when done correctly so that it is an active process (Manyak, et al., 2014; Taylor, Mraz, et al., 2009), vocabulary learning can be time consuming (Manyak, et al., 2014). Therefore, teachers are constantly looking for ways to fit as much instruction as is possible in the short time they have for class. The digital word wall, as presented here, allows teachers to maximize their instructional time.

References

Creswell, J.W., & Plano Clark, V.W. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Graves, M.F. (2004). Teaching prefixes: As good as it gets? In J.F. Baumann & E.J. Kame’enui(Eds.), Vocabulary instruction: Research to practice (pp. 81-99).New York: The Guilford Press.

Graves, M.F. (2009). Teaching individual words: One size does not fit all. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Harmon, J. M., Hendrick, W. B., Wood, K. D., Vintinner, J., & Willeford, T. (2009). Interactive word walls: More than just reading the writing on the walls. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 52, 398-408.

Manyak, P.C., Von Gunten, H., Autenrieth, D., Gillis, C., Mastre-O’Farrel, J., Irvine-McDermott, E., Baumann, J.F., & Blachowicz, C.L.Z. (2014). Four practical principles for enhancing vocabulary instruction. The Reading Teacher, 68(1), 13-23.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: An evidence based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Retrieved on June 29, from: http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/nrp/smallbook.htm

Taylor, D.B., Mraz, M., Nichols, W.D., Rickelman, R.J., & Wood, K.D. (2009). Using explicit instruction to promote vocabulary learning for struggling readers. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 25, 1-16.

Wesche, M., & Paribakht, T.S. (1996). Assessing second language vocabulary knowledge: Depth versus breadth. Canadian Modern Language Review, 53(1), 13-40.

Yearta, L.S. (2012). The effect of digital word study on fifth graders’ vocabulary acquisition, retention, and motivation: A mixed methods approach. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.