Chase Young

Katie Stover

Bethanie Pletcher

Authors: Chase Young (Texas A & M University – Corpus Christi), Katie Stover (Furman University), and Bethanie Pletcher (Texas A & M University – Corpus Christi)

Do you remember making dioramas? Many of our classmates thought it was fun to transform an ordinary shoe box into an inanimate three-dimensional representation of a story. Sadly, we did not. But to us, the reading effort was not worth the reward. Fortunately, times changed and shoebox technology advanced. Imagine walking into a first grade classroom and observing students expressing their reading comprehension authentically with digital tools and sharing their learning with the world beyond the classroom. We think a digital approach to reader response is more efficient than going door to door with a diorama and certainly more suitable for the 21st century. We dedicate this strategy to students who precociously evaluate the varying benefits of reader response activities, and to teachers looking to motivate even the most resistant readers.

The rapid appearance of the Internet and the continuous development of new Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have changed the nature of literacy and the way we communicate (International Reading Association, 2009; Leu & Kinzer, 2000; Leu, Kinzer, Coiro, & Cammack, 2004). With this constantly evolving definition of literacy, it is essential that teachers prepare students for the demands of new literacies through the integration of ICTs into the curriculum (International Reading Association, 2009; Lankshear & Knobel, 2006; Zawilinski, 2009). The ability to read, write, and communicate online require additional skills and strategies beyond the traditional (International Reading Association, 2001).

The New London Group (1996) suggests the need for a broader view of literacy beyond the traditional language based approaches. New digital tools change the way text is created, distributed, and communicated (Lankshear & Knobel, 2003), as students construct, share, and access information using a range of literacies. Meaning is generated and negotiated through face-to-face and digital interactions (Lankshear & Knobel, 2007). Thus, literacy is viewed as a collaborative and multifaceted process (New London Group, 1996). The participatory nature of ICTs promotes collaboration among Internet users (Karchmer-Klein & Harlow Shinas, 2012; Laru, Naykki, & Jarvela, 2012).

These new literacies allow students to interact with content through various modalities. For instance, rather than solely reading or writing printed text, students can engage with technology that incorporates audio and visual literacies. In this way, students determine how to convey information in many ways. The interactive nature of digital literacies increases active construction of knowledge. Furthermore, with the adoption of the Common Core State Standards (2010) across much of the United States, there is a greater emphasis on the integration of technology, including using the Internet to produce and publish a range of writing.

We offer this article to help educators conceptualize the potentials of new literacies in the classroom where traditional types of reading and writing practices are often emphasized. We share one versatile and engaging application known as Explain Everything as a tool to bridge both approaches in the classroom setting. What follows is how one class used this application to create online book trailers.

Explain Everything

Explain Everything is an iPad application that allows users to create slideshows using graphics, drawings, or pictures. The then narrates each slide to match the pictures. The final show is compiled and produced into a movie that can be shared in various ways, such as Facebook, Email, YouTube, or simply saved on the device for future viewing.

You may be thinking, “What’s the difference between this and PowerPoint?” In our experience, it takes a great deal of time and effort to teach students how to effectively use such programs, but we have seen students in Kindergarten successfully create class projects with Explain Everything. So, now your mind is probably racing with the potential educational applications. We have used it in many ways, including publishing essays and fictional stories, illustrating audio journals, and the strategy shared here—creating book trailers.

Using Explain Everything to Create Book Trailers in the Classroom

The students have already read the text and written the book review (Dalton & Grisham, 2013). They are now ready to create a digital book trailer using Explain Everything (or a similar application). To help increase independence and guide their projects, the students answer these questions along the way.

Should I use images from the web, my own drawings, or photos that I take? Here, students determine the best source of graphics for their slides. Often times, they will use all three on any given slide. For example, they may download a picture of Superman and draw the setting around him or take a picture of a classmate and draw in the cape and Superman symbol. In any case, students decide which pictures/graphics/drawings will be suitable for their narration.

Do my illustrations match my narrative? The students are required to illustrate each page. There is no limit to the number of pages needed; however, creating too many slides eliminates the coveted “quickness” of this application. Once the pages are properly sequenced and represent what the student has written, the student moves into the next step.

Have I practiced my narration? It is imperative that students are exposed to good examples of movie and book trailers to accomplish this step. The students should strive for that unique movie trailer narration, overflowing with expression to capture the audience’s attention and leave them in suspense. Once the student can read the trailer with appropriate expression, he/she is ready to record. This is done by pressing the record button, reading the text intended for the particular page, and stopping the recording. The student then progresses to the next page and repeats this procedure until all slides include narration. Upon completion, the student has the option to share the final production.

Classroom Example

Consider the following example that comes from the first author’s second grade classroom. Two students worked together to create a book trailer for Maybelle in the Soup (Speck, 2007). After learning about book trailers, including the style, content, and purpose, the students began discussing the guiding questions and working on the iPad.

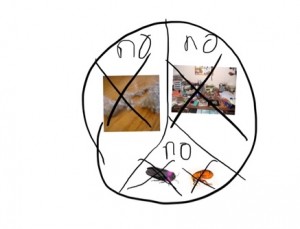

Should I use images from the web, my own drawings, or photos that I take? The girls decided to use pictures from the web. However, in the introduction, they determined that Maybelle was a cockroach that lived under the refrigerator, and decided to use multiple photographs for the illustration. They copied and pasted cockroach and refrigerator images from the Internet and situated them on the slide to fit the oral description (Figure 1).

Do my illustrations match my narrative? The students accomplished this goal by utilizing pictures that fit their narration. For example, on one slide the students quoted characters from the book with “No dust, no mess, and absolutely, positively NO BUGS!” and created the corresponding illustration in Explain Everything (Figure 2). Again, the students decided to use a combination of drawing and photos from the web.

Have I practiced my narration? After adding visuals, the students read and reread their lines, much a like a rehearsal for a performance. They even decided that in some spots they would read in unison and in others take turns. Having watched the final video, it was clear that they practiced, as the video possessed strong elocution that entertained audiences. In this case, these second graders shared their book trailer on the teacher’s class YouTube channel. Following is the script for their book trailer.

Student 1: There are two main characters. Their names are Maybelle and Henry.

Student 2: There are two evil characters as well. Their names are Mr. and Mrs. Peabody. Student 1&2: They always say, “No dust, no mess, and absolutely positively NO BUGS!” Student 1: Maybelle wants to taste something that has not hit the floor.

Student 2: The next day, the Peabodys made mock turtle soup. Maybelle wanted to try it and almost got spotted.

Student 1&2: Will she survive or will she be caught? Read Maybelle in the Soup to find out. Don’t forget to read Maybelle in the Soup by Katie Speck!

Toward Independence

After producing a couple book trailers as a class, and reflecting on students’ productions as a group, the class created a book trailer workstation. Here, students read books independently and developed book trailers. Using a workstation (or center) for these projects worked well because iPads are limited in many schools. Also, students completed the entire task independently and uploaded their own work. Teachers can later view the student productions as well as share the masterpieces with students’ families and friends near and far.

Conclusion

Although we really enjoy the Explain Everything App, there are likely other similar kid-friendly applications. However, with any application used to make book trailers, the task provides a digital experience that requires students to engage in multiple literate processes. For example, students are essentially creating detailed summaries (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000) and leaving out the resolution of the story to create suspense. So, in order to render a quality production, they need a deep understanding of the text. Students also engaged in an authentic writing experience, as they focused on embedding voice into their writing (Culham, 2011; Dorfman & Cappelli, 2007). In addition, the need for expression in the narration requires students use their prosodic skills to convey the appropriate meaning and tone of their chosen stories. In the end, students have a lot of fun, enhance their technological skills, and share learning via the Internet with other classrooms, teachers, friends, and family. By offering students digital opportunities, they are able to expand their learning community beyond classroom walls into virtual learning spaces (Larson, 2009, p. 646).

After the students reached independence and we added the “book trailer” workstation, it became the most highly anticipated destination. Students read voraciously to prepare themselves for it. As an unintended positive consequence, the strategy was naturally differentiated—every student, regardless of reading ability, created book trailers. In fact, the students collectively created over 100 book trailers in three months. And, as we guessed, not one of them lamented about the absence of a diorama project.

References

Culham, R. (2011). Reading with a writer’s eye. In T. Rasinski (ed.), Rebuilding the Foundation, Effective Reading Instrution for the 21st Century (pp. 245-270). Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Dalton, B. & Grisham, D.L. (2013). Love That Book: Multimodal Response to Literature. The Reading Teacher, 67(3), 220–225. doi: 10.1002/TRTR.1206

Dorfman, L. R., & Cappelli, R. (2007) Mentor texts: Teaching writing through children’s literature, K-6. Portland, Maine: Stenhouse.

International Reading Association. (2001). Integrating literacy and technology in the curriculum: A position statement of the Intenational Reading Assocation. Newark, DE: Author. Retrieved from http://reading.org/downloads/positions/ps1048_technology.pdf

International Reading Association. (2009). New literacies and 21st century technologies: A position statement of the International Reading Association. Newark, DE: Author. Retrieved from http://www.reading.org/Libraries/position-statements-and-resolutions/ps1067_NewLiteracies21stCentury.pdf

Karchmer-Klein, R. & Shinas, V. H. (2012). Guiding principles for supporting new literacies in your classroom. The Reading Teacher, 65(5), 288-293.

Lankshear, C. and Knobel, M. (2003). New Literacies: Changing Knowledge and Classroom Practice. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Lankshear, C. and Knobel, M. (2006). New Literacies: Everyday Practices and Classroom Learning (second edition). Maidenhead and New York: Open University Press.

Lankshear, C. and Knobel, M. (2007). Researching new literacies: Web 2.0 practices and insider perspectives. e-Learning, 4(3), 224-240.

Laru, J., Naykki, P., & Jarvela, S. (2012). Supporting Small-Group Learning Using Multiple Web 2.0 Tools: A Case Study in the Higher Education Context. Internet And Higher Education, 15(1), 29-38.

Leu, D. J., & Kinzer, C. K. (2000). The convergence of literacy instruction with networked technologies for information, communication, and education. Reading Research Quarterly, 35(1), 108-127.

Leu, D. J., Kinzer, C. K., Coiro, J., Castek, J. & Cammack, D.W. (2004). Toward a theory of new literacies emerging from the Internet and other informational and communication technologies. In R. B. Ruddell & N. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (5th ed., pp. 1570-1613). Newark, DE. International Reading Association.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of State School Officers. (2010). Common core state standards for English Language Arts & literacy. Washington, DC: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Offices.. Retrieved from http://corestandards.org/assets/CCSSI_ELA%20Standards.pdf

New London Group. (1996). A Pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1) 60-92.

Zawilinski, L. (2009). HOT blogging: A framework for blogging to promote Higher Order Thinking. The Reading Teacher, 62(6), 650-661.

Literature Cited

Speck, K. (2007). Maybelle in the soup. New York: Henry Holt and Company.